Superstitions are having hard times in our modern always progressing world. It is no longer easy to fool someone with a myth or a beautiful legend from childhood. But how about this one: have you ever heard that a thunderstorm could curdle milk?

A correlation between thunderstorms and the souring or curdling of milk has been observed for centuries. As early as in 1685 the first clue was written down in the book “The Paradoxal Discourses of F. M. Van Helmont: Concerning the Macrocosm and Microcosm, Or the Greater and Lesser World, and Their Union” [1]:

“Now that the Thunder hath its peculiar working, may be partly perceived from hence, that at the time when it thunders, Beer, Milk, &c. turn sower in the Cellars … the Thunder doth everywhere introduce corruption and putrefaction”.

By the beginning of the 19th century there had been numerous attempts to find theories of a causal relationship. [2-7] They all were not plausible, many even contradicting. Later, after refrigeration and pasteurization became widespread, eliminating bacteria growth, interest in this phenomenon almost disappeared. While the most popular explanation remains that these occasions are only a correlation, we would like to draw the reader’s attention to some of the suggested theories.

In order to understand what actually happens with milk during a thunderstorm we would need to know (i) what processes are behind the milk souring and (ii) what accompanies thunderstorm, e.g. lightning. While the latter is not yet entirely clear to scientists, [8] the simplified picture of the first point we will cover in the next few paragraphs.

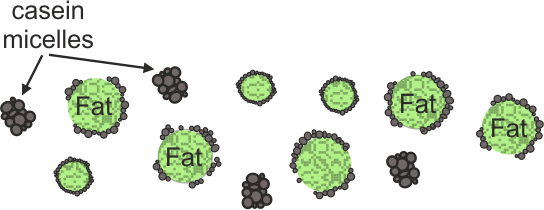

Figure1: Schematic image of casein micelles covering fat globules within milk as a colloid solution.

Fresh milk is a textbook example of colloid – a solution consisting of fat and protein molecules, mainly casein, floating in a water-based fluid. [9] The structure of milk is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1. Fat globules are coated with protein and charged phospholipids. Such a formation protects the fat from being quickly digested by bacteria, which also exist in milk. Casein proteins under normal conditions are negatively charged and repel each other so that these formations naturally distribute evenly through the liquid. Normally, milk is slightly acidic (pH ca. 6.4-6.8), [10] being sweet at the same time due to lactose, one of the other carbohydrates within the milk. When the acidity increases to pH lower than 4, proteins denature and are no longer charged. Thus, they bind to each other or coagulate into the clumps known as curds. The watery liquid that remains is called whey.

The acidity of milk is determined by the bacteria which produce lactic acid. The acids lower the pH of milk so the proteins can clump together. The bacteria living in milk naturally produce lactic acid as they digest lactose so they can grow and reproduce. This occurs for raw milk as well as for pasteurized milk. Refrigerating milk slows the growth of bacteria. Similarly, warm milk accommodates bacteria thrive and also increases the rate of the clumping reaction.

Now, we can think of a few things that may speed up the souring process. The first one could be ozone that is formed during a thunderstorm. In one of the works it was shown that a sufficient amount of ozone is generated at such times to coagulate milk by direct oxidation and a consequent production of lactic acids. [2] However, if this were the case, a similar effect would occur for sterilized milk. The corresponding studies were carried out by A. L. Treadwell, reporting that, indeed, the action of oxygen or oxygen and ozone coagulated milk faster Ref. [2]. But the effect was not observed if the milk had been sterilized. The conclusion drawn from this study was that the souring was produced by unusually rapid growth of bacteria in an oxygen rich environment.

In the meantime, a number of other investigations suggested that a rapid souring of milk was most likely due to the atmosphere that is well known to become sultry or hot just prior to a thunderstorm. This warm condition of the air is very favourable for the development of lactic acid in the milk. [3, 4] Thus, these studies were also in favour of thunderstorms affecting the bacteria.

A fundamentally different explanation was tested by e.g. A. Chizhevsky in Ref. [5]. It was suggested that the electric fields with particular characteristics produced during thunderstorms could stimulate a souring process. To check this hypothesis the coagulation of milk was studied under the influence of electric discharges of different strength. Importantly, in these experiments the electric pulses were kept short to eliminate any thermal phenomena. Eventually, the observed coagulation for certain parameter ranges was explained by breaking of protein-colloid system in milk due to the influence of the electric field.

Other experiments investigating the effect of electricity on the coagulation process in milk turned out to be astonishing. [6] When an electric current was passed directly through milk in a container, in all the test variations, the level of acidity rose less quickly in the ‘electrified’ milk samples compared with the ‘control’ sample. Which contradicted all the previous reports.

To conclude, while there is no established theory explaining why milk turns sour during thunderstorms, we cannot disregard numerous occasions of this curious phenomenon. [7] What scientists definitely know is that milk goes sour due to bacteria – bacilli acidi lactici – which produce lactic acid. These bacteria are known to be fairly inactive at low temperatures. Which is why having a fridge is very convenient for milk-lovers. However, when the temperature rises, the bacteria multiply with increasing rapidity until at ca. 50°C it becomes too hot for them to survive. Thus, in pre-refrigerator days, when this phenomenon was most popular, in thundery weather with its anomalous conditions the milk would often go off within a short time after being opened. Independently of the exact mechanism, i.e. increased bacteria activity or breaking of the protein-colloid system, the result is – curdled milk.

Should you ever witness this phenomenon yourself, do not be sad immediately. Try adding a bit brown sugar into your fresh milk curds…

— Mariia Filianina

Read more:

[1] F. M. van Helmont Franciscus “The Paradoxal Discourses of F. M. Van Helmont, Concerning the Macrocosm And Microcosm, Or The Greater and Lesser World, And their Union” set down in writing by J.B. and now published, London, 1685.

[2] A. L. Treadwell, “The Souring of Milk During Thunder-Storms” Science Vol. XVIII, No. 425, 178 (1891).

[3] “Lightning and Milk”, Scientific American 13, 40, 315 (1858). doi:10.1038/scientificamerican06121858-315

[4] H. McClure, “Thunder and Sour Milk.” British Medical Journal vol. 2, 651 (1890).

[5]V. V. Fedynskii (Ed.), “The earth in the universe” (orig. “Zemlya vo vselnnoi”), Moscow 1964, Translated from Russian by the Israel Program for Scientific Translations in 1968.

[6] W. G. Duffield and J. A. Murray, “Milk and Electrical Discharges”, Journal of the Röntgen Society 10(38), 9 (1914). doi:10.1459/jrs.194.0004

[7] “Influence of Thunderstorms on Milk” The Creamery and Milk Plant Monthly 11, 40 (1922).

[8] K. Litzius, “How does a lightning bolt find its target?” Journal of Unsolved Questions 9(2) (2019).

[9] R. Jost (Ed.), “Milk and Dairy Products.” In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (2007). doi: 10.1002/14356007.a16_589.pub3

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milk