Imagine you are sitting at a table during lunch and your friend or colleague smiles at you. What do you do? You reflexively return a smile. You do not think about it. Indeed, you are also returning a smile if your mind is otherwise occupied. When someone smiles at us, we (usually) return a smile. This happens automatically, around 300 ms after the original smile. It enhances our mood and eases the start of a potential conversation. The underlying phenomenon of the reflexively returned smile is mimicry, i.e. the automatic imitation of a just observed behaviour. Thereby, we must distinguish mimicry from intentional imitation. If we deliberately decide to return a smile to be polite, we intentionally imitate. If we unintentionally and even unconsciously raise the corners of our mouths, we mimic. Solely the observation of a smile suffices as trigger. Accordingly, mimicry can be defined as “a phenomenon where merely observing another’s behaviour elicits a corresponding action in the observer”.1 Thereby, the returned smile, i.e. the corresponding action in the observer, must not completely match the original behaviour. Mimicry can be subtle. Barely raising the corners of the mouth already counts.1,2

Mimicry is not restricted to smiling, even though smiling has a special role as an affiliative signal (as we shall see later). It may be surprising as it happens without conscious awareness, but mimicry takes place in almost every social interaction. Have you ever wondered why you have to yawn as soon as someone else yawns? The answer is mimicry! Unlike most mimicry reactions, yawning is too obvious to be missed. People mimic facial expressions, verbal characteristics, emotional responses, motor movements such as yawning and even health-related behaviors like smoking. Hence, mimicry can be divided into four subsections:6-8

| 1 | Behavioural mimicry: The mimicry of mannerisms, posture, gestures and motor movements, e.g. face touching, foot shaking and handshake angle & speed. Here, the behaviour is repeated in up to 3-5 seconds. |

| 2 | Verbal mimicry: The mimicry of speech characteristics and patterns, such as speech rate, utterance duration, latency to speak or accent. Already newborn babies verbally mimic by crying after hearing another baby cry. |

| 3 | Facial mimicry: The mimicry of emotional as well as neutral facial expressions. Mimicking a facial expression can help to understand the underlying emotions as the muscle movements result in facial feedback, which enables emotion recognition. Accordingly, facial mimicry can lead to emotional mimicry. |

| 4 | Emotional mimicry: The mimicry of emotional expressions. Contrary to the mimicry of most gestures emotional mimicry is intrinsically meaningful because emotional expressions signal socially relevant information and behavioural intentions.2 |

Why do we mimic such a huge variety of gestures and expressions? When we return a smile, we send a social signal. We want to get along or even affiliate with our opposite. We know from experience that smiling enhances our mood and the mood of our opposite and makes us feel closer to each other. The research not only confirmed the affiliative consequences of mimicking a smile but of mimicry in general. In 1999, the chameleon was chosen as a metaphor for unconscious mimicry:9 Just as chameleons change their color to blend in with their environment, humans alter their behaviour to blend in with their social environment.

The so-called “chameleon effect” was described as a social glue that helps to bind interaction partners together. Mimicry facilitates liking, affiliation, empathy and feelings of closeness and can help to understand emotions. It promotes important aspects and needs of social life. Therefore, it is not surprising that mimicry is the default in most social interactions. As mentioned in the beginning, being occupied otherwise does not restrain us from mimicking a smile of a friend. Indeed, a study10 from 2016 revealed that participants under cognitive load mimic the smiles of positively described persons automatically. Additionally, behavioural mimicry even increases under cognitive load. The default character of mimicry is supported by the fact that neither the mimicker nor the mimicked person notice anything.

Does this imply that we always mimic our surroundings? No! Even though we can not consciously control the mimicry reactions, our underlying intentions shape the amount of mimicry we display. We do not want to affiliate with everybody and always. Some situations and constellations will lead to less mimicry. For example, negatively described persons are not mimicked. That fits our experience. Imagine someone you do not like smiles at you. Imagine you are in a bad mood and do not want to engage in social interactions. In both cases, you will not return a smile.

Individual differences play a role, too. Extroverts and adults with secure attachment styles mimic more than introverts and adults with insecure attachment styles, respectively.

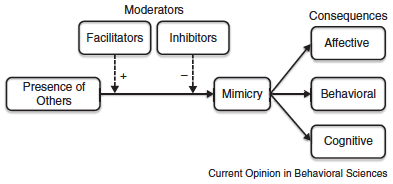

The different factors, which increase or decrease the amount of mimicry in social interactions, are called “moderators” (see Figure 2).6,7 These moderators include our inner motivations and attitude as well as external circumstances that shape mimicry. We already met the most important moderators: the goal to affiliate and pre-existing rapport, you rather mimic a friend as opposed to someone you do not like. We also mentioned mood and emotion: if you are in a bad mood, you will not return a smile.

The goal to affiliate manifests in different ways, for example, through the need to belong. Experiments from 200811 investigated if and how exclusion by strangers leads to an increase of mimicry. Participants who were excluded during an on-line cyberball game mimicked a subsequent partner more. They used mimicry to bond with someone new and, thereby, to recover from exclusion. To test the selectivity of mimicry with regard to the need to belong a second experiment was set up. Female participants got to know the gender of the other players and, thereby, if they belonged to the in-group (just female teammates) or to the out-group (just male teammates). After being excluded, they interacted with a female (in-group confederate) or a male (out-group confederate). In the no-exclusion control condition, participants did not play at all. Females that were excluded by females and afterwards had the chance to restore their status inside the group, due to interaction with another female, mimicked the most (see Figure 3). They used mimicry as a way of saying: “I am too just like you”. Hence, mimicry is used selectively, flexibly and strategically. It occurs more often if it holds promise.

In general, we mimic persons of our group, i.e. in-group members, to a greater extend compared to persons that do not belong. (Not surprising considering that we mimic those we like more!) The group can be fixed, as in the case of gender, or arbitrary. Letting 4-6-year-olds choose a group by choosing a color, increased their mimicry of adults belonging to the same color. Those adults wore shirts in the corresponding color and the belonging was pointed out. It follows that already children act like little chameleons to blend in with their social environment.12

It is a small step from group membership to similarity. For example, sharing the same name or agreeing on various viewpoints promotes mimicry, too. In addition, people mimic attractive persons to a greater extend. (I do not know about you, but most people rather bond with the handsome.) However, being closely committed to someone else lowers this effect. Mimicry can communicate romantic interest and the lack thereof can shield a relationship. We can thus recognize the goal to disaffiliate as an inhibitor.6

Another inhibitor is the lack of morality. Recent studies13 investigated the effect of morality compared to sociability or competence-related information. The authors argue that morality has a primacy on decisions about whom to trust. Being trustworthy is the key information we look for before engaging in interaction and, therefore, it affects affiliation goals. Consequently, the authors tested if morality has a leading role in influencing mimicry. Before meeting a confederate, participants read letters describing a situation in which the confederate acted morally/immorally (returning/keeping a found wallet) as opposed to friendly/unfriendly or competent/incompetent. The confederates, in turn, were instructed to perform three specific movements (rubbing the arm, touching the face, moving the head) during the subsequent, recorded conversation. Independent judges rated the extend to which mimicry occurred. Only the description as immoral lead to a decrease. The unfriendly or incompetent described confederates were not mimicked less. This result confirms the power of morality in affecting mimicry.

Now, we acquired a well-rounded overview of the inner factors that shape mimicry: the goal to affiliate, pre-existing rapport and liking, similarity and morality. Against this background, it is not surprising that mimicry itself creates affiliation, feelings of closeness, liking and trust between the involved individuals. This is a strong statement. It implies, that mimicry shapes our social lives or rather our relationsships and their origins. (No relationship without liking.) Since mimicry is a central part of interactions, we developed expectations on its right amount. Imagine someone meticulously mimics your behaviour. Accurately moving the arm like you, touching the face on the exact same spot you touched yours. Will you feel closer to this person or will you feel shivers running down your spine?

We see, there are exceptional cases in which mimicry does not increase liking. For example, mimicking unfriendly behaviours casts a poor light on the mimicker. Other examples are mimicking out-group members or disliked persons. On the other hand, mimicking an out-group member decreases prejudice on the side of the mimicker. That could lead to a win-win situation or at least a trade-off, because mimicked individuals become more prosocial. Here, we see one of the behavioural consequences indicated in Figure 2: mimicked people often act more helpful towards the mimicker as well as towards others. In the eyes of the mimicked individual, the mimicker appears to be more persuasive. Consequently, mimicry can alter our behaviour as consumer, too. Salespersons that mimic costumers achieve greater success.

Cognitive consequences can be convergent thinking (being mimicked) or divergent thinking (not being mimicked). Mimicked persons are better at recalling positions of objects and (maybe) they conform more likely to stereotypical expectations. Mimicry fosters learning. Learning to appropriately behave in your social environment goes hand in hand with preferentially mimicking in-group members. You better act like an in-group member to catch the bodily and emotional reactions selected by your group. In that sense, mimicking someone signals: “I value you as a good source of information about suitable behaviours.” Mimicry may also help to understand the emotions of our opposite, but to explore that, we must further investigate emotional mimicry first.6,7,14

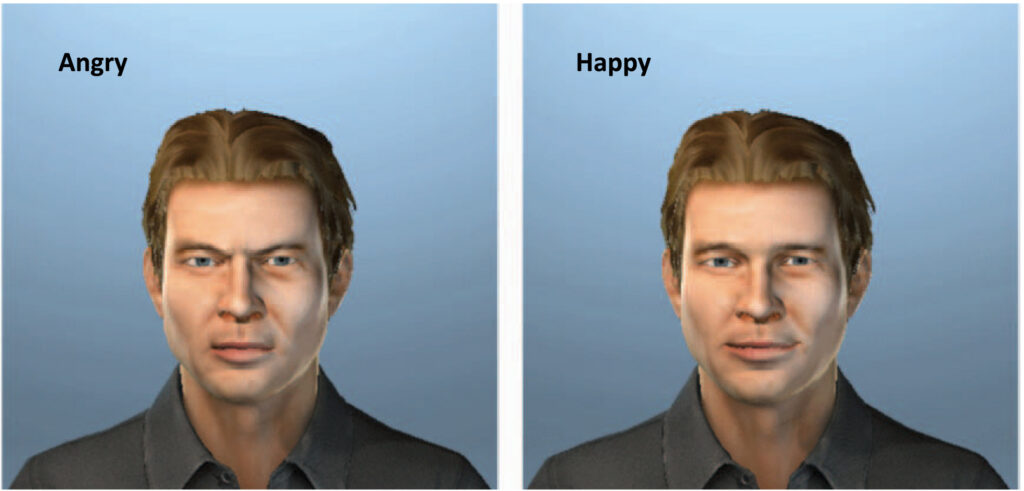

As facial emotional mimicry is subtle (see Figure 4) it is difficult to spot. Furthermore, it is fast, it occurs within 300-500 ms.2 To cope with that, it is measured via facial electromyography (fEMG). When muscles are contracted, they elicit electrical impulses, which are detected by the electrodes of the fEMG. FEMG even reveals expressions below the visible threshold. However, faces are not infinitely large and, thus, the number of electrodes that can be applied is restricted. On the other hand, emotional expressions can involve several muscles. That is one reason why research often focuses on the expressions of anger and joy. Frowns and smiles are usually determined through the activity of the corrugator supercilii (“frowning muscle”) and the zygomaticus major (“smiling muscle”). Another reason is the importance of these emotions. Smiling is a representative of affiliative expressions (e.g. happiness and sadness) and frowning is one of antagonistic expressions (e.g. anger and disgust). In order to signal our affiliative intentions, i.e. to say: “I like you”, we should particularly mimic affiliative expressions and refrain from mimicking antagonistic expressions. Mimicry of smiles is often present even with a lack of affiliative intentions. Smiling as strong affiliative signal may suffice to motivate affiliation and thus mimicry. Seeing only the eye region of a smiling face did not prevent participants from a mimicry response. Furthermore, priming neutral expressions with emotions leads to mimicry of the alleged happy and sad faces. It follows that we do not simply mimic muscle movements but rather the meaning behind them.2

That mimicry reflects meaning is supported by an experiment from 2018.1 Participants played games with an android (the robot not the operating system) either as their teammate or as their opponent. The outcome of the game was communicated through the expressions of the android (“smiling” = android won, “frowning” = android lost). Participants being teammates of the android reacted with spontaneous mimicry as expected. Participants being opponents reacted incongruent to the android’s expression reflecting their own emotional reaction to the outcome. Interestingly, the timing of the facial responses as well as their magnitude were equal. The teammates being opponents reacted as fast as the others. They displayed “counter-mimicry” and, thereby, mimicked the meaning the observed expression had for them. Additionally, we see how strategic context reshapes spontaneous mimicry. The same applies for social context. A study from 20141 highlights the flexibility of mimicry in the context of power. The mimicry reactions of participants depended on their status. Everyone mimicked a frown of a high-status person in under 1 s. Participants with low status displayed a smile just after the frown (2-4s) generating a pattern of mimicry followed by counter-mimicry. Participants with high status mimicked the smiles of inferiors, but not of coequal participants. They only responded with a smile among themselves as they counter-mimicked angry expressions. In summary, context affects the meaning of expressions and impacts mimicry.

Can we understand the emotions of our interaction partner by mimicking his or her expressions? Theories supporting this hypothesis are called “embodiment theories” and claim that higher-level processing is grounded in the sensory and motor experiences of the individual. While observing (or thinking about) a behaviour one can reenact or mimic that behaviour in order to promote conceptual processing.1

| Indeed, mimicry helps to distinguish between true and false smiles. In a study from 2014,15 participants wore plastic mouthguards to restrain them from smiling and to block their mimicry reactions. They watched videos from persons smiling to amusing or neutral stimuli, hence, showing true or fake smiles respectively and rated the genuineness of the smiles on a scale from 1 to 5 (1=fake smile, 5=true smile). To account for the possibility that wearing a mouthguard may be distracting, the participants in the control group had to firmly hold a stress ball. Additionally, in a third group |

(free) participants wore a finger heart rate monitor to make them nearly as aware of their bodies as the participants wearing the mouthguard. The mean ratings of all groups are shown in the following figure.

We clearly see that blocking mimicry has an influence on recognizing false smiles. True smiles were rated less genuine and false smiles more genuine compared to the control groups.

So, did we figure out how people decode emotions of others? Not quite. Contrasting indications exist. People with Mobius syndrome, which causes facial paralyses, are in no way inferior when it comes to recognizing emotions. As their ability to mimic facial expressions is always blocked, they may developed alternative strategies to understand emotions. Anyways, we can not state that mimicry always leads to emotion recognition, but at least these phenomena are not detached from one another.1

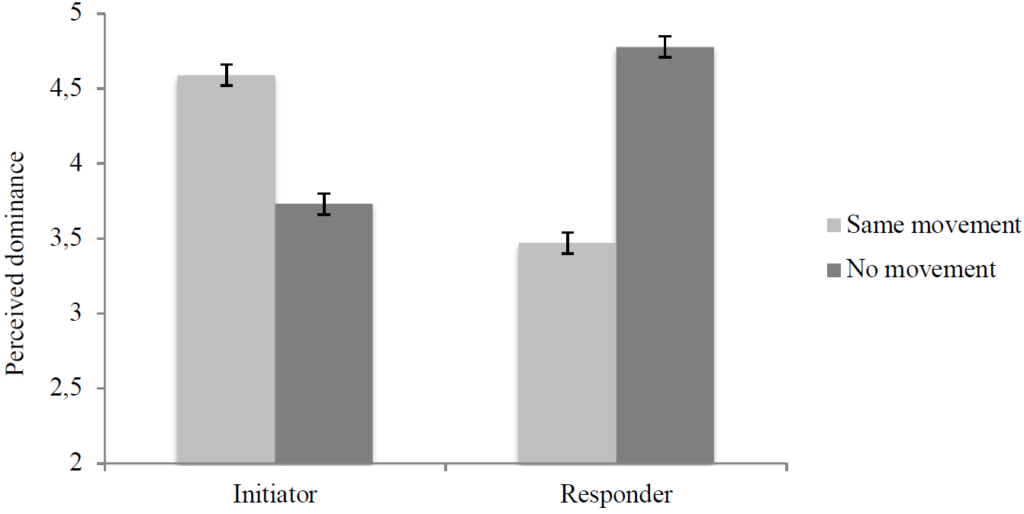

Maybe you have already noticed that the research mainly focuses on the dyad, the mimicker and the mimicked. What about the other persons around? This issue was addressed in a study from 2020.16 The authors argue that the mimicked person is the initiator of a movement and, therefore, gets to “lead” the mimicker. In the eyes of third party observers, the mimicker should look like a “submissive chameleon”. In a series of experiments participants watched different videos of two interacting persons and rated their dominance. (The videos are accessible https://osf.io/wtzrf/?view_only=7e79c6ab20874e49ad992b22a7f8ebfbhere.) In the same movement condition the video showed one person mimicking movements of the other, namely, touching the hair or touching the chin.

The results are displayed in Figure 6. The mimicker, i.e. the “responder”, was rated as less dominant, which meets the expectations. In the absence of mimicry (no movement condition), the pattern flipped and the initiator appeared submissive. (Your movements are not followed? You are in no way in control.) A second experiment concluded: a mere action-response pattern (action followed by different movement) as well as the actual matching of the movement creates the submissive appearance of the responder.

Mimicry is automatic and it happens unconsciously. We can not switch it off if we want to be perceived as dominant. Furthermore the price would be too high, since mimicry smooths the interaction of the dyad. To be more precise the mimicry of affiliative signals serves interaction quality, whereas antagonistic mimicry does not.1 (You are frowning at me and I am frowning at you, I am wondering why interaction quality is low).

We interpret emotional signals and answer them by revealing our emotional intentions through mimicry. Consequently, mimicry has a huge impact on our social lives: it helps to build or maintain social bonds. Mimicry promotes relationships of all kinds and creates effective social groups. Even though the mimicker appears submissive in the eyes of a third person, the positive consequences of (affiliative) mimicry are astonishing. In other words, there are good reasons for the world to smile with you.

Read more:

- Andy Arnold and Piotr Winkielman, 2021. The mimicry among us: Intra- and inter-personal mechanisms of spontaneous mimicry. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 44:195-212.

- Ursula Hess, 2020. Who to whom and why: The social nature of emotional mimicry. Psychophysiology, 58(1):e13675

- Jozef Turóci, CC BY 2.0, https://www.flickr.com/photos/43412438@N07/4843352919

- ESA/S.Bierwald, CC BY-SA IGO 3.0, https://www.flickr.com/photos/37472264@N04/14656564138

- Beth Scupham, CC BY 2.0, https://www.flickr.com/photos/22519875@N08/7311993342

- MTanya L. Chartrand and Jessica L. Lakin, 2013. The antecedents and consequences of human behavioral mimicry. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1):285-308. PMID: 23020640.

- Korrina Duffy and Tanya Chartrand, 2015. Mimicry: Causes and consequences. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 14.

- Korrina Duffy and Tanya Chartrand, 2017. Moral Psychology, chapter From mimicry to morality: The role of prosociality. The MIT Press.

- Bargh JA Chartrand TL, 1999. The chameleon effect: the perception-behavior link and social interaction. J Pers Soc Psychol.

- Heidi Blocker and D. McIntosh, 2016. Automaticity of the interpersonal attitude effect on facial mimicry: It takes effort to smile at neutral others but not those we like. Motivation and Emotion, 40:914-922.

- Jessica L. Lakin, Tanya L. Chartrand, and Robert M. Arkin, 2008. I am too just like you: Nonconscious mimicry as an automatic behavioral response to social exclusion. Psychological Science, 19(8):816-822. PMID: 18816290.

- Sabine Hunnius Johanna E. van Schaik, 2016. Little chameleons: The development of social mimicry during early childhood. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 147:71-81.

- Michela Menegatti, Silvia Moscatelli, Marco Brambilla, and Simona Sacchi, 03 2020. The honest mirror: Morality as a moderator of spontaneous behavioral mimicry. European Journal of Social Psychology, 50(7):1394-1405.

- Liam C. Kavanagh and Piotr Winkielman, 2016. The functionality of spontaneous mimicry and its influences on affiliation: An implicit socialization account. Frontiers in Psychology, 7:458.

- Wood A Rychlowska M, Cañadas E, Krumhuber EG, Fischer A, and Niedenthal PM, 2014. Blocking mimicry makes true and false smiles look the same. PLoS ONE, 9(3).

- Oliver Genschow and Hans Alves, 2020. The submissive chameleon: Third-party inferences from observing mimicry. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 88:103966. Link to videos: https://osf.io/wtzrf/?view_only=7e79c6ab20874e49ad992b22a7f8ebfb